WHY IS THE BIBLE A COOKIE RECIPE?

What ‘the word of God’ actually refers to, and how we often misunderstand it. 5-7 min. read.

So, we have a recipe for amazing Christmas cookies. All women in my family know it by heart. They use the same or very similar ingredients in similar proportions and they teach their daughters to make the cookies. One auntie makes the cookies with almond milk because of her kids’ lactose intolerance. Another auntie tries to stay fit and reduces the amount of sugar a bit. During the times of real socialism, some grandma used a ‘chocolate-like product’ instead of actual chocolate, which was hard to get back then. Some women in the family actually wrote down the recipe just in case they get forgetful as they age. What they wrote differs slightly – because of reasons mentioned above, and then because someone wrote a name of a butter brand, someone wrote just ‘butter’; some listed the ingredients in Polish, some in Silesian. Some added some explanation to details of the procedure of baking, while for the rest it was too obvious to mention. One titled the recipe as ‘grandma Stasia’s cookies’ even though she wrote down her own variant (one without baking soda) – she learnt making the cookies from Stasia, so she didn’t see an issue with that. She didn’t think she was compromising anything or that she was being dishonest by claiming grandma’s authority. In the end, all recipes written by all aunties were meant to be a point of reference to the same, universal cookie recipe, and the changes were not perceived as ‘unfaithfulness’ to, or ‘corruption’ of the original recipe, normally passed on verbally. All of them pointed to recognisably the same amazing Christmas cookie.

Do you see what I’m trying to do?

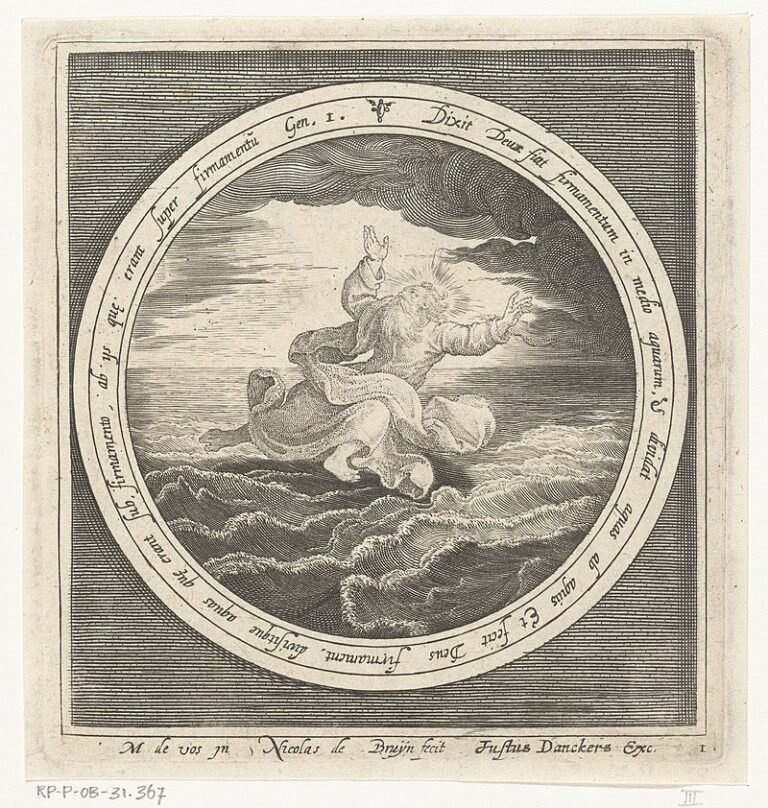

The Bible is a cookie recipe. The logos, the word of God is not a particular version of the recipe written down – it is the cookie. The recipes may change slightly depending on times and preferences of a cook, yet as long as our favourite Christmas cookie is recognisably the same cookie, all is fine.

It may sound strange to us for one very simple reason we miss with ease:

We can read and we can access written stuff all the time at virtually no cost. Just think about what you are doing right now.

Discussing a chapter of the Bible with a friend, we can check the very text in a few seconds just by touching a screen. If things are still not clear enough, we can look up different translations and the original Greek text in a concordance with each word extensively explained and defined. If we, hopeless nerds, still want more, we jump to articles or videos with the world’s best scholars explaining every nuance of the text. All done in a couple of minutes.

Imagine how long it would take in the 2nd century CE.

As shocking as it may be, back in the Roman Empire, or ancient Israel, no one had a nice copy of the Bible at home, on their smartphones, or in an eco-leather zipped cover, handy and nice to carry around.

Stories and wisdom were passed orally. Repeated by different people to different audiences in different circumstances, they naturally differed in details. Memorisation was much more vital in the process, as only a few had access to eyewitnesses or written sources. Because of the role of memorisation and verbal transmission, it was much more important for the stories and wisdom to make their points in a clear and memorable way, rather than to keep the wording or the sequence of events exactly the same every time the story was told.

Sure, some people wrote things down. Yet they were still people functioning in a primarily oral culture. While written documents were ultimate points of reference, stored safely and owned by communities, their authors did not think they possessed the only right version of the core message, and they did not think it was wrong to adjust the text to their times and audiences, just like reducing or replacing an ingredient doesn’t cancel the cookieness of a cookie, while it may make baking easier and the final product tastier for a particular person.

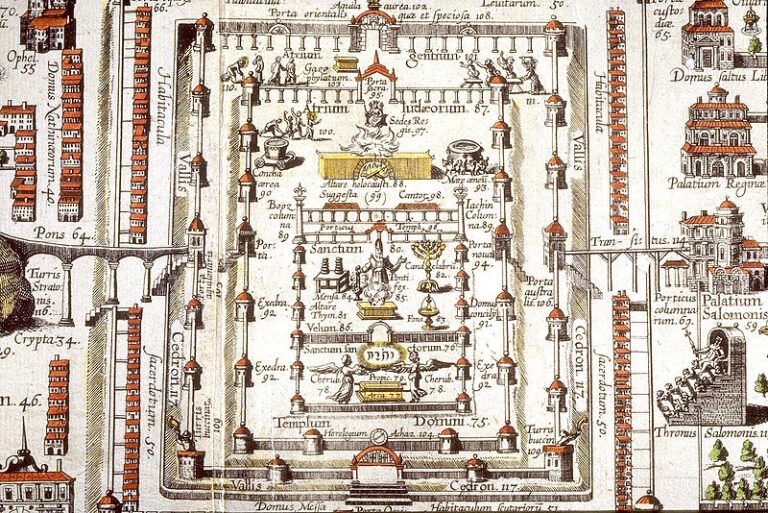

So, we’ve got at least two written recipes of the ‘Davidic dynasty’ cookie: in books of Kings and Chronicles – each tasting slightly different.

We’ve got a written ‘Isaiah cookie’ recipe: some of it likely going to the original Isaiah, while large chunks date back to his students, more remote followers, or just people identifying with his baking tradition, yet making the dough in completely different times (if you wish to find more about the authorship of ‘Isaiah’, use the benefits of our written culture and check Wiki).

And of course we’ve got four separate written recipes of the ‘Gospel cookie’ – each slightly different in ingredients, and none really written by the actual recipe author, who preferred sharing it verbally with crowds, until some people really, really didn’t like the flavour.

And so it goes, and so it is all fine. Having the ‘cookie recipe view’ in mind, we are much less likely to suffer a dissonance when bumping into seeming ‘contradictions’, ‘discrepancies’ and ‘inconsistencies’. We know the cookie is still the cookie.

Don’t we?

The Christmas cookie story is 100% made up and I didn’t even invent the cookie metaphor – I only extended it a bit. Most of the thoughts above and the metaphor itself are taken from ‘The Lost World of The Scripture’ by John H. Walton and D. Brent Sandy.

The book is great, perspective-expanding and I highly recommend it.

Which doesn’t mean I don’t have any questions and reservations. Namely:

When does a cookie lose its cookieness or becomes a different cookie? How do we draw a line? Who draws the line?

Who has the right to claim grandma Stasia’s baking authority? Or well, apostle Paul’s, or prophet Daniel’s authority?

We have not-Paul-written Paul’s letters in the Bible and we have a few more of them outside of the Bible. The first group is considered inspired and canonical, the other isn’t.

We have ‘prophecies’ in the book of Daniel very clearly not written by him and being extremely precise and accurate to the exact point of time when they were written (backwards prophecies, yes) and going wildly inaccurate for what was the future back then.

The canon of the Scripture didn’t just materialise. It was set by whole bunches of rabbis and bishops. Did they know more or less than we know about the texts? Were they inspired and divinely guided, like the texts authors?

Lots of space for talking and thinking. Lots of space for a case to case analysis and debate.

But you didn’t expect an article on a blog named ‘The Christian Agnostic’ to make a feel-good point and close the topic.

Or did you?

Now you can leave disappointed.